Artificial Larynx

This project constitutes the research I conducted during my Ph.D, which you can download a copy of the manuscript here (FR), and the defence presentation here (EN) or here (FR).

Context

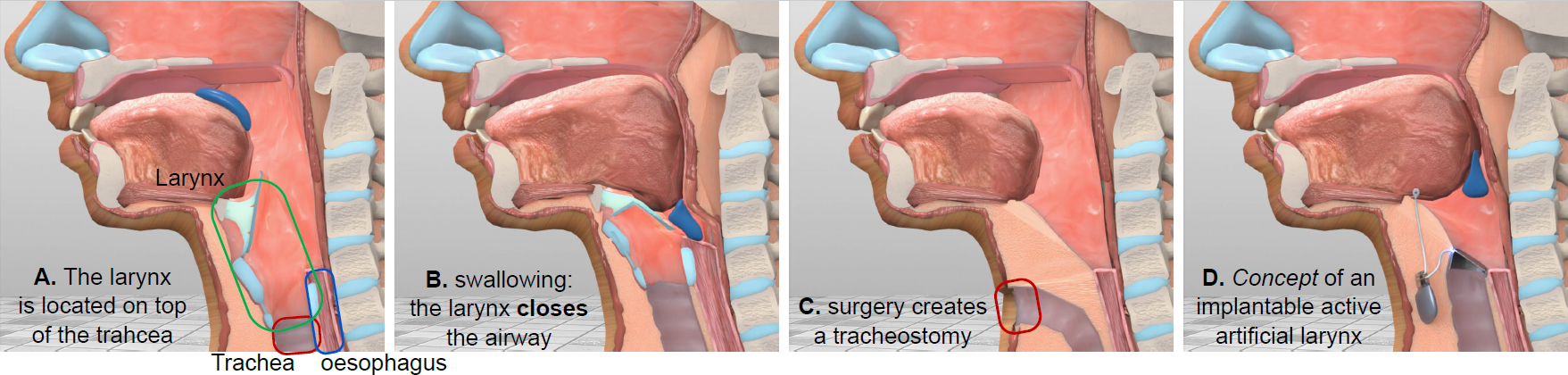

Located in the throat, above the trachea, and sharing a common passage with the esophagus, the larynx is a multifunctional organ primarily involved in phonation, respiration, and swallowing. It contains the vocal cords, is capable of regulating the flow of air entering and exiting the lungs, and offers a complex airway protection mechanism during swallowing, to prevent any misdirection of the food bolus. In cases of advanced cancer, the standard treatment involves the complete removal of the larynx, called total laryngectomy. Consequently, the functions of the larynx are lost and partially and suboptimally restored through surgery, with the creation of a tracheostomy. This involves suturing the trachea to the front of the neck, effectively addressing the loss of the laryngeal airway protection mechanism but also permanently separating the airway from the digestive tract.

After the surgery, the patients no longer breathe through their nose and mouth, resulting in the loss of smell, air warming, filtration, and speech. Repositioning the trachea to its original position would allow for a better restoration of laryngeal functions and would improve patients’ quality of life. However, this requires to replicate the airway protective mechanism. In this regard, the first implantation of an artificial larynx in humans took place in 2012. The prosthesis was entirely passive, made of titanium in a tubular shape, and reproduced the airway protective mechanism through a concentric valve mechanism. The patients could breathe and swallow, but only under medical supervision, and food residues were still able to partially enter the trachea. This partial success opens up new possibilities, and the addition of an active protective mechanism would allow to forcibly and temporarily close and protect the trachea during swallowing, through the design of an active implantable artificial larynx. However, to activate such a prosthesis, a real-time and implantable swallowing detection system is required, by measuring physiological signals. The feasibility of such a detection system has been the subject of my research.

Also, let us specify that all of this work was carried out in close collaboration with an otorhinolaryngologist surgeon, within the framework of a clinical research protocol for validation of our research carried out on humans, and conducted at the Grenoble hospital center in France.

Results

The apparent ease of swallowing hides the considerable complexity of the process, involving more than 25 pairs of muscles that contract in a sequential manner over the course of a second. While the physiology of swallowing has been extensively studied, no research had explored how an implantable active artificial larynx could be integrated into this process. To adress this gap, I conducted a comprehensive survey sumarizing the current knowledge on the swallowing physiology, the consequences of total laryngectomy, and the current swallowing detection methods. It also established the four main criteria for the feasibility of such a prosthesis. The main and decisive criteria being the earliness of the detection, given that no implantable active artificial larynx can be considered safe if the swallowing is detected when the airway is already at risks of food aspiration.

A. Mialland, I. Atallah, and A. Bonvilain - “Toward a robust swallowing detection for an implantable active artificial larynx: a survey.” - Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing

We then identified specific anatomical structures to be measured within the neck, on the hypothesis that they would provide qualitative data in terms of earliness and swallowing detection performances. My survey suggests the stylohyoid (SH) and the posterior digastric (PD) neck muscles to be great candidates, but previous researches have only conducted indirect measurements via imaging methods, because of the difficulty to get precise measurements of each of them. So, my following contribution was on the development of a new measurement method to record the SH and PD muscles activity. We used two needles containing microsensors that allow to record their electrical activity, called intramuscular electromyography (iEMG) measurement. The challenge was to precisely locate each muscle to insert the needles, which was performed by the otorhinolaryngologist surgeon. Then, two other sensors were used. First, the sound of swallowing was recorded to extract precise swallowing events and especially define a temporal detection limit, after which the airway would be at risk of aspiration. Second, a group of superficial muscles, called submental muscles, can easily be accessed using surface electromyographic (sEMG) electrodes, placed on the skin. The beginning of their activity has been shown to mark the beginning of swallowing.

A. Mialland, B. Kinsiklounon, G. Tian, C. Noûs et A. Bonvilain - “Submental MechanoMyoGraphy (MMG) to Characterize the Swallowing Signature” - Innovation and Research in BioMedical engineering

A. Mialland, I. Atallah, and A. Bonvilain - “Stylohyoid and posterior digastric measurement with intramuscular EMG, submental EMG and swallowing sound.” - Bio-Inspired Systems and Signal Processing.

Once the needle-based approach was validated by an ethical committee, we recorded the signals on 17 people, that each performed 4 swallowing tasks (liquid, solid, …) and 13 non-swallowing tasks (head movements, jaw movements, …), that I later compared with statistical analysis. The results first show that both SH and PD muscles activate at the beginning of swallowing, which would give the maximum amount of time until to the temporal limit to run a detection algorithm and close a protective mechanism of the airway. It also allowed to estime the available time until to the temporal limit to be 427 milliseconds on average. Second, the SH muscle showed a net predisposition for swallowing, only closely followed by mastication, and the PD muscle had the vast majority of its activities located before the temporal limit. These statistical analyses were conducted separately and can be found in the following papers.

A. Mialland, I. Atallah, and A. Bonvilain - “Stylohyoid and posterior digastric timing evaluation” - Body Sensor Networks

A. Mialland, I. Atallah, and A. Bonvilain - “Stylohyoid and posterior digastric recruitment pattern evaluation in swallowing and non-swallowing tasks” - Innovation and Research in BioMedical engineering

I then assessed these muscles within a real time swallowing detection strategy. I used the signals to build machine learning algorithms and evaluate both their detection performances and earliness. The results show that, as suggested by the statistical analyses, the SH muscles allowed for a net improvement in detection performances in comparison the common approaches, and the PD muscles consistently allowed for the earliest detection, before the temporal limit. In addition, the difficulty to differentiate swallowing from each non-swallowing tasks were evaluated and most of them were easy to differentiate. However, the tasks closely related to swallowing, such as mastication or jaw movements, were the hardest to discriminate, which gives important clues on what tasks or family of tasks to focus on for further improvement. This analysis can be found in the following paper.

A. Mialland, I. Atallah, and A. Bonvilain - “Stylohyoid and posterior digastric potential evaluation for a real-time swallowing detection, with intramuscular EMG” - IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics

One final contribution concerns the time it would take for an implantable active artificial larynx to actuate a swallowing detection and airway protective systems. Whatever the ability of the anatomy to provide qualitative data, the system itself should be able to temporarily close the airway as fast as possible. So, to formally and practically establish the viability of an implantable active artificial larynx, the following paper gathers what I discussed so far to develop a laboratory prototype of such a prosthesis, as a proof of concept. I established its requirements and core implementation, and its final conception was performed by engineering students in electronics and mechanics, that I supervised within internships. So, given that it constitutes a specific sub project within my thesis, the detailed can be found in the Laboratory Prototype page I dedicated to it. In short, it reproduces the requirement of an implanted system by, first, implementing real time detection algorithms on microcontrollers and, second, developing a protective mechanism that reproduces the mechanism of the larynx. The full prototype could be actuated in less than 30 miliseconds, from the moment it starts to process incoming data, to the full closure of the protective mechanism. This timing easily fits within the available time defined by the SH and PD muscle activities, with regard to the temporal limit.

A. Mialland, E. Bouchet, A. Diallo, and A. Bonvilain - “Implantable active artificial larynx: timing evaluation of a laboratory prototype” - IEEE International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics